|

My father is an artist, and fond of saying unexpected pithy things out of the blue (when he isn't saying something silly which I then find myself obliged to argue with...although at such times one can never be certain he is actually serious. He likes to play at that, too). He once said to me, pointing in front of him, "Suppose this is the most logical or rational direction to take." (By this he meant: in life.) He then shifted the direction he was indicating by five degrees or so. "The best course, however, is usually just a little bit off."

I think it is natural to think of

emptiness or

nothingness as symmetrical and void, the complement or inverse of

being. But perhaps it is better to think of nothingness as

not as featureless

as one would first imagine; similarly, perhaps being is

not as heavy as it at first appears.

Somewhat tangential to the subject of being and nothingness.

All of which reminds me of something completely different:

the vast quantum mechanical energy which permeates even a vacuum, and

speculation about tapping into it.

Heather Anne was very kind to mention me on her delightful and fascinating site which, as I mentioned in my first entry, was one of my

chief inspirations to start this.

What is the relationship between constraints and creativity? I read an article a few years ago about the

relative lack of productivity of artists and scholars awarded fellowships by the

Getty Research Institute; these prominent personalities are given everything

one would think they would need to be productive: money, a place to live and work, pleasant

surroundings, weekly social gatherings with the other Fellows,

and no distractions. Curiously, comparatively little work seems to emerge from those

who participate in the program. Perhaps artists do not thrive when they are given

everything they think they would need?

Ironically, the odd legacy of J. Paul Getty has produced a complementary example as well. (I say odd because Getty seemed to be fond of collecting an eccentric mishmash

of art objects which one gets to witness thrown together at his museums). The (new) Getty Center was

designed by the architect Richard Meier, and though it has been controversial (many people

totally detest it), there is no question that Meier put a lot of careful thought into

its design. Though I can't say that looking at it

from a distance is particularly inspiring, there is no question that

walking through the building is a rich experience. Clearly, Meier spends a lot

of time thinking about how people actually move through and use his spaces; and

he carefully designs the experience to work at the human scale. Traversing the buildings, you are rewarded with a series of unexpected

vistas of other parts of the structure or of Los Angeles (though I grew up in L.A. I never particularly thought of it as having the

capacity to produce vistas until I visited the Getty Center). He thinks carefully about how museum patrons would want to experience

the collection, moving through it section by section, and so he divides up the

space into several smaller buildings, rather than creating a huge monolith. In this case,

the reason to visit this museum is to experience and use the building itself.

But what's particularly interesting about Meier is that he is famous for making

all of his buildings either white or off-white; he is also famous for being

absolutely particular about lining everything up perfectly; every block of stone is lined up

on a perfect grid, and even the very

layout of the tables in the cafeteria are placed in a rectilinear layout. He consciously limits certain variables

so that he can focus on optimizing many others.

So, to elaborate on yesterday's note. I went with Susan to a book reading by Susie Bright (currently

on tour promoting her new book, Full Exposure) at the

downtown SF Stacey's bookstore. Susan had a professional interest in the reading, since

she recently got a gig writing her personals advice

column for Willamette Week,

the Portland alternative weekly (they ran an ad in the

newspaper for the job, and she submitted an application on a lark, thinking her chances of being

picked were something close to that of winning the lottery, but much to her surprise...)

Susie Bright is, of course, famous for her frank and down-to-earth writing on the subject of sexuality.

While she spoke in her charming, sensible, and relaxed way about a topic that still

confounds many of us, I found myself thinking about the various unresolved questions and issues I have about

sexuality (questions about monogamy, jealousy, shame,

and other things) which I have placed on the back burner of my consciousness for

years. It seemed easier to confront these things while listening to her speak.

I also heard Ed Osborn give a talk and presentation I asked whether he thought there was a

relationship between his emphasis on systems and the fact that he works

with sound; he said he started as a composer, and

in music one deals with systems all the time: even a single musical instrument is a system. Furthermore, the process of getting a piece performed is complex and involves dealing with social and

political systems.

Which reminded me of a very funny passage from

Frank Zappa's autobiography in which he discusses all of the trials and tribulations

he had to go through to get the

London Symphony Orchestra to perform his classical compositions, as well as his great

rant regarding the sad state of the music industry today, how experimental work

is almost impossible to get published, and his views of the social and political

reasons why.

I got my first incoming link from one of my favorite weblogs, Alamut! Thanks very much, that made my day.

Had a very interesting time today, first at a book reading by Susie Bright in SF, and

later on at an engaging talk (at the mysterious Interval Research) by Ed Osborn, an installation artist who specializes in sound spaces. Still in travel mode, will

post more about this very soon.

Went to an entertaining benefit book reading/panel discussion/party for the Independent Publishing Resource Center of Portland, Oregon. The event was sponsored

by chickclick.com,

K Records,

and

Reading Frenzy (an excellent zine and book shop), with panelists from

Hip Mama (publishers of entertainment and resources for mothers),

BUST (the "voice of the new girl order"), and

Danzine (a zine and collective for exotic dancers).

I actually had little idea what the event was about (I was invited by a friend, Mim),

I just thought it was going to be a book reading of some kind, but it

turned out to be a lively event organized by

(mostly) enthusiastic twenty-something women primarily for women, though

there were a few other men besides me (I didn't feel out of place). The panel

discussion was quite interesting. Those who were active on the Web

were quite excited about the possibilities of Web self-publication (I agreed with them there). They have already had significant success so far.

I'm off to the Bay Area for a week and a half.

Bought The Matrix DVD today. Yes, I couldn't resist. It looks and sounds absolutely

fantastic on my laptop DVD drive (the drive was a $50 option and well worth it)

and on the TV via the S-Video cable.

In honor of my Baudrillard rant yesterday, I will mention that Simulacra and Simulation

is featured in an early scene of The Matrix (it's the hollowed-out book from which Neo

grabs the illicit computer disc), open to the chapter "On Nihilism."

Okay. As of this writing, it isn't actually September 22 yet. Which reminds me of an acquaintance who used to get The New York Times delivered on the West Coast in the late evenings, before the date printed on the paper (by that time on the West Coast the

New York Times had already been put to bed). Reading tomorrow's news today makes one feel a tad like

Doctor Who.

I like to eat

Sweet Tarts while watching movies, yet many theatres fail to stock them.

Perhaps it's because they are cheap and long-lasting, and don't go well with the absurdly

overpriced movie theater popcorn ($3 for a bucket full of mostly air?)

Had a conversation on the following subject while eating lunch on the deck:

Like many, I find

Baudrillard ever-fascinating, insightful, and funny. But I wonder if he fails to mention (perhaps on purpose) some things regarding

the precession of simulacra? He seems to be saying that not only have we entered an age

where it is understood that the map is not the territory, but in fact we now have

only maps: simulacra which live entirely within their own terms, no longer

referring to a basic reality.

However, it occurred to me that even if we accept this picture, we still

have an image of simulacra which are not

closed, nor are they self-contained, and they are fragile. They are not closed: there

is always an element of the unknown (and unknowable) about them, and thus always an

element of surprise---the unexpected (a sign that is not in the system of signs

within the simulacrum) could appear (if you are paying attention)

and suddenly there can be the opportunity for a

break, a crack

in the shell, through which the infinite could pour in, unbidden. You look up

and something disturbing and uninvited tells you that you may be

dreaming: you realize

there is a larger world. Of course this larger world is itself not the real, but

just another simulacrum, but because of these moments of apparent transcendence we create the myth of the real.

You can never wake up to the real, but you can never be sure when you

might be induced to engage in the gesture of waking up: a gesture that can repeat without limit. This gesture destroys the old simulacrum and replaces it with a larger one which includes the old one as a sort of toy. It seems to me

that it is for this reason we have invented the distinction between the map and

the territory: even though all we have is the replacement of one simulacrum for

another, as each one shatters in turn.

Currents of the postmodern in premodern Japan.

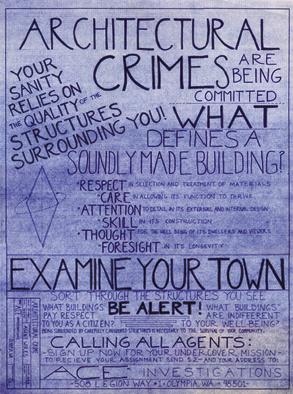

I want to argue for the development of a new architecture, one which transcends the usual categories of "art" and "engineering" (and does not merely juxtapose the two, or try to find the one in the other, as in "the art of engineering" or the "science of art"), and which, in the spirit of the architect Christopher Alexander,

attempts to balance seemingly incommensurable forces in elegant ways, applied to design

problems in a wide variety of fields. Maybe this

isn't new at all, but is just what architecture was always about, or at least could

have always been about.

Observed while helping Emily buy her new VCR: Sony has finally found the antidote for

the History

Eraser

Button...

the "Reality Regenerator".

Speaking of which, my friend Doug has a theory that he is never

going to die (subjectively). He came up with a story to illustrate this idea which

he called Feynman's Last Experiment. The notion is that

Richard Feynman (dying of cancer at the time Doug

thought of this), on his deathbed, would

come up with an experiment to determine if Everett was right in his

Many-Worlds Interpretation

of quantum mechanics, a theory

which states (roughly) that everything that can happen,

does, in some universe. If Everett was right, there

was a universe in which Feynman never dies. So, as a final

experiment (which, alas, only Feynman could observe),

he would simply wait to see if he would somehow miraculously survive...

Interestingly, after Feynman had died, Doug heard a rumor that in

fact, near death, the great physicist had

said "Now I'll find out if Everett was right..."

Even if some mad scientist does blow up the world (or if

some high-energy physics experiment destroys the universe---scroll

halfway down or search for "destroy the universe"), some universes would survive. So, if some mysterious event (an explosion, then a

power failure, then...) repeatedly stops a new high-energy experiment from commencing...

Interesting interview with poststructural philosopher Mark C. Taylor. A bit difficult

to read in Web form; it seems they reproduced the print layout exactly,

which doesn't make for a comfortable online experience. However, the content is

worth a look.

I am deeply indebted to Heather Anne Halpert

for inspiring me with her myriad connections...

|

about

his audio installation pieces. I found it most interesting that he

thinks primarily in terms of systems (both physical and social), rather than isolated

objects. Much of his work involves the construction of systems, interactive and

otherwise, with an aural emphasis (though he claims he doesn't focus on the visual

impact of his work, it is often visually interesting). He feels the art world tends

to focus on objects which is an easier paradigm for them to deal with, because it is easier to

buy and sell objects than systems with moving parts, etc.

about

his audio installation pieces. I found it most interesting that he

thinks primarily in terms of systems (both physical and social), rather than isolated

objects. Much of his work involves the construction of systems, interactive and

otherwise, with an aural emphasis (though he claims he doesn't focus on the visual

impact of his work, it is often visually interesting). He feels the art world tends

to focus on objects which is an easier paradigm for them to deal with, because it is easier to

buy and sell objects than systems with moving parts, etc.